Download this article as PDF

Abstract

At the forefront of measures adopted by North African states in response to the Covid-19 pandemic was the deployment of information and communications technology (ICT). Digital technology is highly important in terms of declared health targets; nevertheless, the adoption of arbitrary, draconian laws that utilise digital surveillance tools in many cases exceeds stated targets in regards to coping with Covid-19 and protecting public health. The pandemic-related measures adopted by North African states deploy digital authoritarian practices and sustain them, with the aim of imposing surveillance and control over the citizens, in violation of their human rights, privacy rights, and public freedoms. An acute danger is posed to the protection of internet freedom, together with heightened risks associated with violations of privacy and the compromise of personal data. Digital surveillance enables governments of North African states to extend their authoritarian reach, by silencing the voices of popular dissent, independent media, and opposition figures. This comes with rising fears that digital surveillance will be sustained beyond the end of the Covid-19 crisis.

Introduction

The advantageousness of the internet in regards to enabling transparency and increasing democratic engagement is widely understood and often taken for granted. Yet the Covid-19 pandemic has witnessed a rise in digital authoritarianism throughout the world. This rise is more pronounced in North African countries, where internet shutdowns, censorship, mass surveillance, and violations of privacy rights have become more frequent, and citizens are not guaranteed digital rights and freedoms. These countries are increasingly providing internet services that threaten democracy, and can even act as a weapon against democracy by facilitating forms of ‘postmodern totalitarianism’.

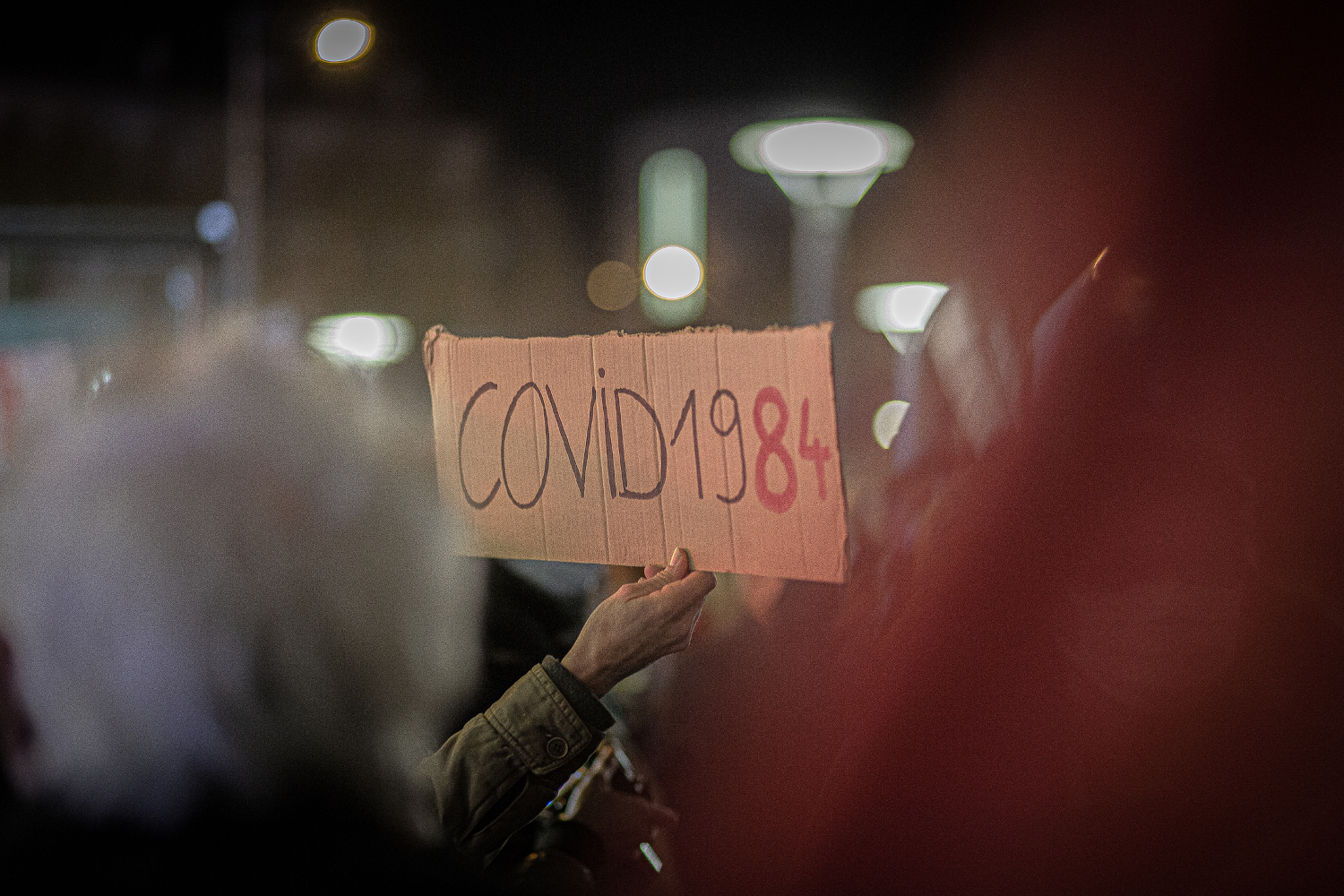

Internet freedom in North African countries has deteriorated dramatically with the emergence of elements of a dystopic future. These elements include the monitoring, control and manipulation of cyberspace to the extent that it resembles 1984 by George Orwell, with ‘big brother watching you. Likewise, it resembles the model of a ‘panoptic community’ as theorised by both Jeremy Bentham and Michel Foucault.[1]

The increasing use of internet in North African countries is perceived by their governments as a genuine threat to their rule. Thus, these governments embarked upon a comprehensive strategy to confront any perceived threat through strong state control, including state control over the internet and media. In the time of Covid-19, state control over the media has intensified, with these countries now witnessing the growth of practices associated with digital authoritarianism, practices that include the prosecution of bloggers and online commentators. Restrictions on information access and free expression not only violate the rights of citizens, but also they also violate the rights of journalists and the media to express and promote opinions and ideas.

The growing threat of protests has not gone unnoticed by North African states, with their keen awareness of the role social media played in the protests’ outbreak. Yet although technology has had an important role in facilitating protests, the authoritarian governments of North Africa are exploiting some of the same technological innovations to suppress popular mobilisation and dissent. Technology is used not only to quell protests, but also to tighten conventional methods of control. Thus, the use of digital repression and the standard means of repression, in ‘real life,’ – such as detention and torture – have concomitantly increased.

The intensification of digital authoritarian practices in North African countries was dictated by the renewed authoritarian tendencies of their governments, which saw the Covid-19 crisis as a once-in-a lifetime opportunity to install the foundations of digital authoritarianism. Such digital authoritarian practices can gain legitimacy among broad segments of society, due to the health goals such practices are purportedly after, and due to fear spreading throughout society. This is evident by the exceptional measures and electronic applications that have been adopted.

In order to approach and deconstruct the topic of this paper, we will rely on a scientific and critical methodology that takes into account the necessity of bringing together the pillars, indicators and arguments that support the growth of digital authoritarian practices in North African countries, in the context of Covid-19. Meanwhile, we will clarify the manifestations of digital authoritarianism by focusing on four countries: Morocco, Egypt, Algeria, and Tunisia. On this basis, one can begin by asking, how do the governments of North African countries exploit panic and uncertainty to extend and enhance digital authoritarian techniques? How do these governments employ laws to restrict and tighten the screws on internet freedom and violate the principle of privacy; the overall objective remaining to silence, suppress, and eliminate critical voices? By highlighting cases from the countries under study, how is the suppression of internet freedom and the violation of privacy carried out? How do feelings of fear (regarding the imminent danger emanating from Covid-19 alongside the legitimate anxiety created by existing authoritarian legacies and new digital authoritarian practices in light of Covid-19) increase the likelihood of the transformation from temporary comprehensive electronic monitoring of citizens into permanent electronic monitoring? In pursuit of answering these legitimate questions, analysis of the subject was undertaken according to the following elements.

Exploiting Panic and Uncertainty to Promote Digital Authoritarianism

Living in the grip of fear is not only about worrying about the present but anticipating more problems in the future. Fear is the opposite of hope. The pandemic striking the world today increases instability as it adds a great amount of uncertainty, and appears to exacerbate an already existing culture of fear. The pandemic also reveals wounds that are deeper than imagined, and according to the political, economic, social and cultural impacts of crises and natural disasters. Public health emergencies and their resultant harms are considered as ideal circumstances for governments and the elite to implement political agendas that would otherwise face great opposition. This issue is not unique or related only to the crisis caused by the Covid-19 virus. To the contrary, it is a policy that has been followed by many national governments for decades. This policy is known as the ‘shock doctrine’, a term coined by activist and author Naomi Klein in her 2007 book The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism. Many ideas, measures, procedures, and laws are latent, waiting the golden opportunity created by a crisis or disaster to come to fruition.[2]

Accordingly, the shock doctrine is the political strategy pursued by North African states to systematically exploit large-scale crises to advance policies that deepen inequality and enrich the dominant interest-based coalitions in these countries. Political and economic elites realise that moments of crisis are their opportunity to push their shopping-list of unpopular policies that further polarise wealth. In moments of crisis, people tend to focus on everyday emergencies to survive, whatever sacrifices and concessions they must make, and they tend to place substantial trust in those in power.

In this context, and in light of the shock, uncertainty, and risks resulting from the Covid-19 crisis, a fear has formed in the public mind: that the coronavirus represents an imminent threat that could reach every person, even in their home. This fear is severely exacerbated by media coverage of the pandemic in many countries. This coverage intends to resuscitate the spirit of ‘trauma,’ by adding an element of drama to the daily news about the pandemic’s spread. This formed a new reality in people’s minds, the main component of which becomes an unconscious or particularly escalating psychosis. This psychosis, caused by a subtly mounting fear of the coronavirus, is no less dangerous than the pandemic itself. People with psychosis lose their ability to critically assess the reality around them and rush in search of salvation from a ‘coming to get me’ coronavirus, to become docile and submissive. As such, one can do anything with these people, and justify any action by ‘fighting the pandemic,’ and they will not resist. For authoritarian regimes, the Covid-19 crisis remains a ripe time to engage in manipulative management in order to legitimise digital authoritarianism.

The advancement of artificial intelligence-powered surveillance in North African countries is the most important development in digital authoritarianism. High-definition cameras, facial recognition, malicious spyware, automated text analysis and big data processing have opened up a wide range of new methods for controlling citizens. These technologies allow governments to monitor citizens and identify opponents in a timely fashion – sometimes in a proactive manner. This is what motivated most North African countries to accelerate the use of new surveillance technologies as long as people are preoccupied with their health safety. Regimes moved steadily towards digital authoritarianism by adopting the Chinese model of intensive surveillance and automatic monitoring systems.

As a result of these trends, certain dangers to internet freedom have materialised and will continue to materialise as governments exploit modern digital applications – which often obscure the underlying risk of ‘digital authoritarianism’ – under the pretext of battling Covid-19. This indicates that the future of internet freedom is increasingly threatened by the tools and tactics of digital authoritarianism. These repressive regimes with renewed authoritarian ambitions have exploited the unregulated spaces in social media platforms and transformed them into tools of political distortion and societal control.[3] On this basis, the function of technologies has been subverted, from digital empowerment of citizens to digital repression.

In Morocco, the General Directorate of Security provided policeman at checkpoints with the ‘Weqaiti’ application on their smartphones in order to control the movement of citizens, which sparked substantial controversy and reaction from society and the human rights movement. The application, which was prepared by a team that included engineers and technicians from the Information and Communication Systems Directorate, enables policemen to view the security checkpoints passed through by citizens, thereby facilitating the process of tracking movements that violate health emergency requirements, and taking legal measures against violators. This application has raised many concerns, as it may mark the beginning of generalised digital surveillance that can potentially be used for political purposes, and may violate the principle of privacy in their practical applications.[4]

In Egypt too, the Ministry of Health and Population announced the launch of the ‘Egypt Health’ application on phones to educate and guide citizens on how to prevent infection from the emerging Covid-19 virus, and how to handle the situation when suspected of contracting the disease. According to a statement by the Ministry, all information and data in the application are approved by both the Ministry of Health and Population and the World Health Organization, and the information is constantly updated according to the latest available data and information. The application also provides the ability to communicate with an accredited medical team to follow up on the symptoms of any person likely to have contracted the infection, and how to act according to their current health condition.[5]

In Algeria, the new technological application ‘Doctor de Zad’ was launched, in the latest step by the authorities to confront the Covid-19 virus. The Algeria Telecommunications Corporation has also developed modern applications that appear to be very effective.[6] In Tunisia, a ‘Protect’ application was adopted to limit the spread of Covid-19. It alerts people in close proximity to infected cases via Bluetooth technology. The Tunisian Ministry of Health stated that the application is available on the Android and iOS platforms of Apple.[7] The Tunisian Ministry of the Interior also uses a ‘robot device’ in the form of a small armoured vehicle equipped with surveillance cameras and a thermal camera, which is controlled remotely. The small vehicle is equipped with a GPS system and roams the streets of Tunisia to monitor compliance with quarantine measures.[8]

New technology strategies, such as so-called precision targeting and deep falsification – digital falsifications that are indistinguishable from original audio, video, or images – will further enhance the ability of authoritarian regimes to manipulate the perceptions of their citizens. Ultimately, precise targeting may allow these systems to allocate content to specific individuals or segments of society, just as the business world uses demographics and behavioural characteristics to personalise ads. AI-powered algorithms will allow autocratic regimes to target individuals with information that strengthens their support of the regime or seeks to counter specific sources of dissatisfaction. Likewise, the production of deep-fakes would make it easy to discredit opposition leaders, in turn rendering it increasingly difficult for the public to know what is real, and sow doubt, confusion, and indifference.

A growing number of digital technologies have been adopted by North African countries to monitor citizens more comprehensively and at lower cost (on top of the usual digital surveillance in normal circumstances). The increasing effectiveness of digital monitoring and control systems has served to double the incentives provided by these governments to support these emerging technologies. Therefore, effective uses of high-tech surveillance will only encourage governments to invest more in improving, expanding and deepening information technology systems, in order to have more control and sway over information in virtual space.

Consequently, these applications concentrate power in the hands of a few, given that these new technologies have proven effective and efficient in triggering a deeper and more widespread surveillance cycle. The efficacy of digital surveillance techniques has been proven relative to maintaining a wide network of informants. Due to governments’ strategy of extending comprehensive monitoring, it may be significantly cheaper and faster to install web traffic checking tools in every major internet portal in the country, instead of deploying informants in the streets. It may also be better to track citizens’ movements through facial recognition by adopting artificial intelligence. It is apparent that authoritarian regimes in North African countries are increasingly reliant upon high-tech surveillance, which is of course more effective than its human alternative.

New technologies are now providing rulers in North Africa with new ways to maintain power, allowing them to automate monitoring and tracking of their opponents in ways that are far less intrusive than traditional surveillance. Not only do these digital tools enable authoritarian regimes to form a wider network of human-dependent methods, they can also do so using far fewer resources. An official needn’t adopt a program to monitor people’s text messages, read their social media posts, or track their movements. Rather, once citizens know that all these things are assumed to happen, they change their behaviour without the regime having to resort to physical repression.

Internet censorship does not differ from traditional censorship with regard to its purpose, which is to control political opposition; that is, internet censorship gives governments the ability to control dissent and censor opposing views on the internet under the pretext of protecting social and political stability. Protecting stability is the most common rationale given by governments to restrict the freedom of their citizens to express opinions, although the genuine and underlying rationale is political censorship and monopoly of power. North African countries imposed strict control as the Covid-19 virus spread by filtering online content for the sake of national security in exchange for allowing wide spaces for content that supports their regimes.

Laws as the Anchor of Digital Authoritarianism

Mounting internet surveillance and control in North African countries is a matter of concern, in addition to being a clear violation of political and civil rights and a threat to human rights and democracy. Legislators in North African countries have steadfastly drafted a large number of increasingly repressive, restrictive and arbitrary laws, which include deterrent and restraining penalties, to apply to social media users in order to impede the exercise of free expression on the internet. The laws carry within them expressions indicative of digital authoritarianism, which is evidenced by the models adopted in North African countries.

Before the Covid-19 crisis, Morocco introduced restrictions to internet freedom in response to protests in some regions in the country, especially the Rif. The security authorities were fully aware of the role played by social media in igniting the protests, and with the advent of the Covid-19 crisis it increased in importance. With the declaration of the state of emergency, many crackdowns were inflicted under the pretext of enforcing the state of emergency and quarantine. Crackdowns were also justified under the pretext of stopping the spread of false news, and were often reliant on vague legal provisions that can be interpreted by the authorities to silence dissent, be it coming from electronic press or citizen journalism. In this context, we find the law on Press and Publication,[9] which imposes financial penalties on anyone who publishes fake news. Yet it is the Penal Code that remains like a sword over the necks of activists and bloggers; restricting freedom of digital expression by stipulating imprisonment penalties. The Penal Code gives law-enforcement institutions wide discretionary powers to tighten their grip on internet freedom.[10]

During the height of Covid-19’s spread, the introduction of Bill 22.20 (regarding the use of social networks, open broadcast networks, and similar networks) raised many concerns about restrictions on freedom of digital expression. Indeed, with the bill ringing alarm bells about whether it will be used to control and manipulate the exercise of internet freedom, there is growing concern that Moroccan society will soon have to face an era of digital authoritarianism instead of digital democracy. This could constitute a broader entry point towards the erosion of civil liberties and democracy in Morocco, and the consolidation of digital authoritarianism, according to which the government exercises control over citizens by preventing them from accessing content or data and restricting them from participating. It could also lead to the realisation of a soft digital authoritarianism considered by researchers as more insidious and slowly rising in prominence. In light of this kind of digital authoritarianism, we find that governments and political parties use data and social media to monitor and spread information and misinformation with the aim of controlling and manipulating the behaviour and ideas of citizens. This happens frequently, but usually without citizens’ consent or knowledge.[11]

In Egypt, the authorities have used several laws in previous years as the basis for pressing charges against activists, most notably: the Telecommunications Law, the Penal Code, and the Law on Combating Terrorist Crimes. The focus has been on charges such as: misusing social media, spreading false news, and joining a terrorist group. The same applies to digital authoritarian practices in light of the Covid-19 crisis to silence the voices of opponents and critics. In addition, there is the Cybercrimes Law, which is used to block websites. According to Article 7 of the law, websites can be blocked for the publication of any content that represents a crime stipulated by the law, provided that it poses a threat to national security or endangers the country’s security or national economy. These are ambiguous or vague terms that can be interpreted and adapted to restrict internet freedom. In addition, blocking websites here includes broadcasts from inside or outside Egypt.

In addition to the Cybercrimes Law, the Law Regulating Press and Media is one of the means deployed by the government to restrict opponents. In Article 19, which was phrased in imprecise and vague terms, law enforcement authorities are granted discretionary power to block websites without being bound by clear criteria. The Supreme Media Council is also granted the ability to block personal accounts on social media. The law as a whole acts as the basis of charges that are more widespread and invasive, as the law for the first time codified the blocking of personal social media accounts – a violation of the provisions of the Egyptian Constitution and international standards protecting the right to freedom of expression.[12]

With Algeria lacking a law on internet freedoms, a set of arbitrary laws is being used to restrict cyberspace freedom, especially with the rising tide of protests that coincided with the Covid-19 crisis. There is Law No. 04-09 which includes special rules to prevent crimes related to information communications technology, which in turn allows electronic surveillance and control. As the crisis intensified, the Penal Code was also amended through Law No. 20-06 amending and supplementing Decree No. 66-156 of 8 June 1966 on the Penal Code, which entered into force on 22 April 2020. The law contains several provisions that are inconsistent with international standards on freedom of expression and freedom of association, especially articles 19 and 22 of the ICCPR, which Algeria ratified in 1989. ‘Up to three years and a fine from 100,000 dinars to 300,000 dinars for whoever deliberately publishes or promotes, by whatever means, false or tendentious news among the public that may prejudice public security or public order. The penalty is doubled in the case the crime is repeated.’ In addition, there is no precise definition of ‘false information’ in the law, which gives the authorities disproportionate and discretionary power to suppress critical content and controversial information, with regard to imprisonment penalties stipulated in Article 196 bis. Electronic surveillance has been further enhanced by the creation of an agency to combat cybercrime, which has raised many concerns among Algerians, as it can be used to violate their rights, privacy and personal data.[13]

As for Tunisia, we find a continuation of the oppressive and arbitrary legislation used during the rule of Ben Ali; this legislation poses an imminent threat to internet freedom. We mention here, for example, the law on building and operating telecommunications services. Its provisions clearly violate the new Tunisian Constitution ratified in 2014, which stipulated greater protection for the privacy of communication data and the prevention of blocking media content before its publication; the law’s provisions also violate international standards for internet freedom.

In addition, there is the media law on journalistic conduct, and the penal code that applies to freedom of expression on the internet, and criminalises defamation. For example, article 54 of Decree No. 115 on Freedom of the Press, Printing and Publishing states: ‘Anyone who deliberately publishes false news that harms the peace of public order shall be punished with a fine of two thousand to five thousand dinars.’ If, however, the publication of false news is deemed as aiming to undermine public security, then the provisions of article 68 of the penal code are applicable, which establish penalties of up to five years in prison for endangering national security.

Cyberspace activists and components of Tunisian public opinion also considered the establishment of the Technical Communications Agency in 2014 as a serious threat to internet freedom. They saw that this agency- whose primary mission is to provide technical support to the judiciary in dealing with and researching information and communications crimes – represents a threat to the privacy of Tunisian citizens and opens the door for a return to the policy of silencing.[14]

In fact, these unfair laws adopted by North African countries will only contribute to perpetuating authoritarian digital surveillance based on shutting down the internet, arresting and monitoring critical and dissenting voices, and heightening the risks of financial penalties on social media and the closure of the virtual political arena against competition. This will inevitably lead to an increase in signs of authoritarianism or authoritarian behaviour that is disruptive to internet freedom, which will consequently result in a gradual erosion of trust in the internet, as well as in the foundations of democracy in general. The impact of restricting internet freedom will have grave consequences, given the limited mechanisms in place to combat this interference: weak institutional maturity, limited checks and balances, fragmented civil societies, opaque regulatory frameworks, and limited advocacy for the private sector. In the absence of strong mechanisms against internet interference, current conditions are conducive to abuse and slippage towards authoritarian rule.

Targeting Internet Freedom and the Principle of Privacy

The term ‘internet freedom’ encompasses a wide range of interconnected human rights, often referred to as ‘digital rights.’ These rights include access to the internet, freedom of expression on the internet, digital privacy and the right to request, receive and transmit information over the internet. While many have argued that internet freedom does indeed constitute a human right, others see it as a tool that can be used to enable other rights. Regardless of which perspective is adopted on this issue, the United Nations has clearly condemned any attempt to prevent or deliberately disable access to the internet, and stressed upon the necessity of human rights in supporting internet governance. The aforementioned rights to internet and information access and exchange, free expression on the internet, and digital privacy are widely included in the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights under article 19; individuals are entitled to freedom of opinion and expression, including the right to receive and impart information and ideas ‘through any media and regardless of boundaries.’ Article 12 states that ‘No one shall be subjected to arbitrary interference with his privacy, family, home or correspondence, nor to attacks upon his honour and reputation. Everyone has the right to the protection of the law against such interference or attacks.’[15]

Personal privacy, which was relatively easy to maintain previously, has become more difficult in the digital age. This means that the loss of privacy is another aspect of the information society to which North African countries have become accustomed. Many internet technology (IT) experts, such as Daniel J. Solov, Simpson Garfinkel and Evgeny Morozov are concerned about how the expansion of the internet threatens an individual’s privacy. In the novel 1984, citizens are taught about the love of a ‘big brother,’ the adoption of constant surveillance, and complete lack of privacy, as a way of life. Today, we willingly and without much regard to governments, provide our information, websites, photos and personal details, even our inner thoughts and feelings to various internet service providers, web pages, social media and online chat forums [16]

Digital authoritarianism violates a basic human right: freedom of expression, and violations of free expression on the internet have been documented in North African countries to varying degrees. Internet control and censorship has in turn strengthened the ability of authoritarian regimes in these countries to maintain their monopoly on political power instead of weakening it. This was reflected in the disappointment of many regarding the failure of the internet and the communications technology revolution to dismantle oppressive regimes.

In Morocco, since the beginning of the pandemic security authorities have been conducting a widespread arrest campaign of citizens who purportedly violated the emergency law or published false news on the internet. This angered many human rights organisations, and the Moroccan Association for Human Rights documented a number of arrests, prosecutions, and trials against the backdrop of publishing a blog, video, or Facebook content.[17] The United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights confirmed that some governments use emergency laws – which were imposed due to the Covid-19 crisis – to crackdown on the opposition and control the people and even prolong their stay in power. Morocco is one of these governments, according to another official in the commission. In addition to arresting hundreds of people, including activists, on charges of ‘spreading false news’ about Covid-19, the Moroccan authorities are pursuing other activists and journalists, on other charges. Perhaps the case of journalist Omar Radi, which is causing widespread controversy in Morocco, is the most recent of these cases.

After being convicted of ‘harming the judiciary’ last March for posting on Twitter criticising the rulings issued against Hirak activists, Omar Radi is currently under investigation for ‘obtaining funds from abroad that have ties to intelligence agencies,’ the Public Prosecution announced. The Public Prosecution’s announcement came two days after Amnesty International published a report claiming that the Moroccan authorities used spyware called Pegasus developed by the Israeli technology firm NSO to spy on Radi’s mobile phone. Meanwhile, Morocco affirmed through its diplomatic mission in Geneva that the measures it has implemented to contain the Covid-19 virus are in line with ‘the rule of law in full respect for human rights.’[18]

In Egypt, no citizen or media outlet was spared repression. For instance, activist Sanaa Seif, sister of prominent activist Alaa Abdel Fattah, was arrested on charges of spreading rumours about the deteriorating public health situation in the country and the spread of the Covid-19 virus in prisons. One day after the arrest of Sanaa Seif, journalist Nora Younis was arrested. Younis is the editor-in-chief of the news website Al-Manassa, which had been blocked in Egypt several times on charges of ‘spreading false news and rumours.’[19] On 17 March, the Egyptian authorities launched a campaign to suppress foreign journalists who published information about the outbreak of the virus, and charged them with ‘repeated intentional defamation’ and ‘professional misconduct.’ The General Information Authority ended the accreditation of the Guardian’s correspondent in the country,[20] and it issued a warning to the correspondent of the New York Times because he reported a greater number of infections than those officially estimated. In addition to the strict laws adopted by Egypt, the virus was used as another pretext to control information and suppress freedom of expression. A campaign of arrests was enabled under accusations of spreading false news. The aim of the arrest campaign, of course, is to divert citizens from the regime’s failures in governance and its mismanagement of the pandemic crisis, in light of a lack of transparency and integrity, and its determination to silence opposition voices.[21]

In Algeria as well, especially after the temporary suspension of protests due to the Covid-19 virus, social media has been used to ensure continuity in expressing protest, opposition and criticism. An example is the broadcast of the International Covid-19 Radio on the internet, which broadcasts a bimonthly program evaluating and criticising the political system. However, the regime has found a way to narrow and tighten the screws on these virtual spaces, similar to how it earlier managed to tighten security and fences in squares and streets, by employing the amended penal code that includes ‘criminalising false news’ in order to preserve ‘state security.’

In this regard, Human Rights Watch documented the ways in which Algeria exploited the emerging Covid-19 pandemic to suppress the protest movement. Since the beginning of the pandemic, courts have sentenced well-known members of the movement, such as Karim Tabbou and Abdel Wahab Fersaoui, to imprisonment for ‘undermining the integrity of the nation’s unity.’ Journalist Khaled Dararni was also imprisoned on the 27 March. Some websites were suspended, and some young people were detained for peaceful activity on the internet. There is no doubt that the Algerian government is trying to silence opposition voices and end the movement, and it does so while insisting that ‘freedom of expression and a democratic climate’ are available in Algeria.[22]

In regards to Tunisia’s record regarding internet freedom before and after the revolution, many fear a return to the less free pre-revolutionary stage, despite Tunisia being at the forefront in terms of internet freedom compared to other Arab countries. This fear stems from the fact that repressive and arbitrary legislation is still in effect, and from the declaration of a state of emergency in the country. This compelled various human rights organisations in Tunisia and abroad to view with suspicion the exceptional measures taken by the government in managing the Covid-19 crisis, especially due to the presence of previous practices targeting freedom of expression on the internet.

Despite the flexibility shown by the Tunisian authorities regarding internet freedom in the time of Covid-19 compared to the rest of the North African countries under study, the most prominent case that preoccupied Tunisian public opinion and human rights actors was that of blogger Amna Al Sharqi,,who was prosecuted in early May and sentenced to six months in prison after circulating online a parody text of the Qur’an. She was charged with ‘insulting the sacred, assaulting good morals and inciting violence.’ At the end of May, Amnesty International had called on the Tunisian government to stop its prosecution of the blogger, viewing it as ‘undermining freedom of expression in an emerging democracy.’ [23] Many have considered that this case brings authoritarian practices back to the collective Tunisian memory – albeit in their digital incarnation. The case is a real trial balloon, and a measure of the maturity of Tunisia’s democratic transition.

Fears of Temporary Digital Surveillance Becoming Permanent

Italian philosopher and academic Rocco Ronchi wrote an article entitled ‘Le virtù del virus’ (The Virtues of the Virus) asserting that the emergency measures imposed to resist the pandemic universalise the ‘state of exception’ inherited by the present from the ‘political theology’ of the twentieth century. This confirms Michel Foucault’s hypothesis that the modern sovereign power employs ‘biopolitics’, viewed as the practices and policies of the governing authority that regulate the human body and population in a common sphere where political power and biology intersect, and in a time of the global spread of capitalism.[24] ‘If Western regimes fail, we will not only see authoritarian surveillance systems that very effectively use artificial intelligence techniques, but also authoritarian systems to distribute resources,’ says Jacques Atay.[25] This surreal and dramatic image is more pronounced in the countries of North Africa. Citizens live at a time exposing the horrors of life and the world’s descent into darkness, with the Covid-19 crisis creating an epic nightmarish tragedy that floods television screens and the media with images of fear, and manifestations of genuine daily anxiety. Daily life has taken on a state of war, and militarisation has become a basic means of controlling the pandemic and indicating war’s dominance in societal values. More specifically, militarisation is a contradictory and tense social process in which the ruling elite organise society to produce violence. The ruling elite in North African countries deploy fearmongering in a way that serves their interests and creates societal demand for digital authoritarianism. Governments are using the pandemic crisis to expand their attack on civil liberties and defeat constitutional rights. They are engineering repression, and the total elimination of the opposition. In light of the adoption of this strategy, the genes of submission to and acceptance of the practices of digital authoritarianism have become further enhanced across broad segments of society across the region.

The Covid-19 pandemic has seen the rise of a new era of digital surveillance and the reshaping of North African countries’ sensitivities about data privacy. Many citizens have welcomed governments’ imposition of digital surveillance and tracking technology ostensibly aimed at strengthening defences against the novel coronavirus. Yet privacy advocates fear governments may not cease these practices after the health emergency ends, with the digital monitoring of citizens continuing and becoming permanent. Nevertheless, citizens’ fear of returning to the pandemic’s anomalous daily situation will inevitably lead to the continuation of many digital monitoring procedures and measures beyond the context of the crisis that justified their creation and implementation. Governments of North African countries will not easily give up valuable resources enabling them to obtain information and personal data to use for practicing social control. They will not spare any effort to push citizens to accept permanent digital surveillance, to which they are already accustomed and reassured by, especially since this digital surveillance was introduced out of necessity to protect public health. Pushing citizens to accept digital surveillance also includes the use of fear, which is considered by governments to be a valid and necessary tactic to attain a greater degree of social discipline and obedience.

There is no doubt that there is a collective will across countries throughout the world directed toward controlling the pandemic. North African countries have also been involved in this endeavour, but not at any price, warned cybersecurity expert Solange Grunty, as the danger of government exploitation of the crisis and the prioritisation of public health both lie in the adoption of surveillance systems that may not be discontinued thereafter. This is tantamount to creating the ‘Big Brother State’ model inspired by George Orwell’s 1984, which is a common metaphor for expressing total surveillance of society. In such a scenario, almost everything is subject to unprecedented censorship, akin to Chinese authoritarianism. With this monitoring implemented, citizens will face with many threats to the protection of their privacy and personal data, and threats to their right of free expression, as discussed earlier. The goal of this surveillance is to create consensus around governance systems by restricting citizens’ ability to express opposing views. Digital surveillance techniques will enable the government to monitor citizens – in an intensive and unrestricted manner- by tracking their movements, habits, and the expression of their ideas. This will contribute greatly to citizens’ practice of self-censorship as well.[26]

The mere feeling of being under constant surveillance will impose self-discipline and compliance amongst individuals in these countries. Evgeny Morozov, a technology researcher, confirms this fear, as he believes that awareness of surveillance, but without knowing how and when, can compel many activists to censor themselves or refrain from behavioural expressions unwanted by the governing authority. The presence of a higher power always potentially watching you, and the consequences of being aware of that presence, captures the essence of the Eurocentric perspective ‘Big Brother is watching you’ and works to sustain it.[27] Problems are always raised regarding the application of states of emergency and the possibility of extending emergency or exceptional measures after the end of crises. This is applicable to North African countries where the authoritarian grip is tightening to a worrying extent, and where the enactment of previous states of emergency have legitimated the concern of exceptional measures lasting indefinitely.

There is no doubt that the current response of North African states may be considered as the right response. And while it may succeed in curbing the spread of the virus, the peoples of the region will face another danger when the virus recedes; namely, authoritarianism in their countries will be much more pronounced than it was before the Covid-19 crisis.

In times of crisis, checks and balances are often overlooked in the name of the executive power. The risk is that these temporary measures (practices of digital authoritarianism) will turn into permanent practices, and governments often exceed what is needed for public health. So there is a genuine risk that enhanced digital surveillance powers will exceed the duration of the coronavirus outbreak and be used for illegal purposes. In this context, Bieber, author of the book Debating Nationalism: The Global Spread of Nations, believes that ‘the current measures may succeed in reducing the spread of the virus and the spread of the pandemic, but the world will face another kind of danger. Many countries will be much less democratic than they were before March of this year, even after the virus threat recedes, and that checks and balances – often – are ignored by the executive authorities in times of crisis, but the danger lies in the scenario where these exceptional temporary measures become permanent.’ [28]

Giorgio Agamben, an Italian philosopher and legal theorist, goes in the same direction with his book The State of Exception. He considers that ‘the authorities use exceptional circumstances to justify the suspension of the law and the possession of absolute power, indicating its transformation into a permanent state even in democratic constitutional systems.’ As Nick Cheesman, a professor of democracy at the University of Birmingham asserts: During crises, the power of the central government generally increases. However, when the crisis ends, that power is not always returned to the public and the lower levels of government.[29]

After the crisis, the predominance of digital authoritarianism will be further enhanced by much of the public’s view that digital authoritarianism succeeded in emergency or exceptional situations, especially in situations when it seemed clear that authoritarian policies or practices made a difference. Thus, digital authoritarianism will be rendered the appreciated and favoured approach during a confrontation. North African countries may not easily give up their authoritarian and repressive measures after the end of the Covid-19 crisis.

Digital authoritarianism renders the coronavirus crisis more dangerous to democracy, and fuels the spirit of authoritarianism, especially if people believe that the only way to combat the disease is through an authoritarian approach, including centralisation of governance and the disruption of state institutions with the adoption of comprehensive digital monitoring. These concerns become particularly acute in countries marked by with a condition of ‘authoritarian stability.’ In practice, this state is embodied in a shift towards a trend of deepening authoritarian practices. In such countries, the political leadership initially accumulates more and more power, removes normative and legal controls that limit their power, and undermines opposition. In the worst cases, it becomes impossible for the political leadership to be removed, even by electoral means and constitutional and legal requirements. Even the average citizen adapts to this condition of authoritarian stability and contributes to strengthening it.

Conclusion

With the proliferation of modern communication technologies, the influence of digital authoritarianism has taken new forms, and internet censorship and control have a detrimental effect on human rights to an increasingly large extent. Authoritarian governments in North African countries were remarkably successful in adapting to the perceived risks posed by the internet to their power. While North African states promote internet use to support economic growth and development, at the same time they have transformed the internet into a tool to control and maintain political stability. Consequently, there has been an increase in internet-related arrests, and at the present time, digital authoritarianism has gained an upper hand over digital liberation.

The Covid-19 crisis has undoubtedly accelerated North African governments’ use of new surveillance technologies. Their stated goal for deploying enhanced surveillance is to track down citizens who may have been exposed to the virus, and they claim that this surveillance is not in itself anti-democratic or inconsistent with protecting privacy and personal data. Yet in predominantly authoritarian contexts, there is a great risk of politically motivated violations that utilise these new measures, especially if they are licensed and implemented without transparency or oversight. The governments of North Africa that prohibit criticism or lack transparency can effectively protect their political position at the expense of public health and safety.

Genuine democracy requires that North African countries break with this abhorrent digital authoritarianism, and instead provide for a protected cyberspace. This entails blocking and rejecting any violations related to personal data and privacy issues, and guaranteeing the right of access to the internet and information. Not least of all, democracy requires the right of free expression to be upheld, including in virtual spaces. Without guaranteeing free expression, security, prosperity and freedom – the fruits of democratic governance – cannot be maintained.

North African countries will need to develop a democratic model of digital governance. To do so, the technology sector, policymaking, and legislation will need to present compelling models for digital surveillance that balance the need for security while continuing to protect civil liberties and human rights. The internet as a virtual public sphere that can enhance transparency, achieve accountability, and form a better relationship between government and citizens must also be supported. This should be an endeavour towards creating a decentralised virtual environment, a ‘purer’ form of democracy, where everyone’s voice is heard and the right to access and share information is freely given.

Openness to digital democracy in North African countries would undoubtedly create a vibrant and active online community. The massive increase in the popularity of direct online communication, especially through social media platforms, can create spaces for the expression of opinions, including oppositional opinions, to a wide audience. It can contribute to presenting more candid ‘critical’ views of the government, companies, and public figures. Traditional media, often under the control of governments and thus limited to transmitting the official or state narrative, will be undermined by the internet’s conspicuous role in diversifying public debate and opening new ways for citizens of North African countries to bypass state-controlled media.

[1] For more on this subject, see: Martin, Aaron K, Rosamunde Van Brakel, and Daniel J Bernhard (2009) ‘Understanding resistance to digital surveillance: Towards a multi-disciplinary, multi-actor framework’, accessed 15 August 2020, shorturl.at/mEMN5.

[2] For more details, see: Klein, Naomi (2006) ‘The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism’, (Toronto: Knopf Canada).

[3] Freedom House (2018) ‘Freedom on the Net 2018: The Rise of Digital Authoritarianism’, accessed 10 August 2020, https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-net/2018/rise-digital-authoritarianism.

[4] Weqaiti App sparked reactions from human rights organisations and on social media platforms. This debate found its way to the House of Representatives, about the extent to which the application conforms to the Moroccan Personal Data Protection Law. In a parliamentary question, a PM asked whether the creation of the file related to personal data processing the movement of citizens during the period of the state of health emergency was done according to a law or regulation, and whether it was ‘submitted to the National Committee for Monitoring the Protection of Personal Data to express an opinion on it’. Interior Minister Abdel Wafi Laftit said that this application is only a phased application, and that the aim of this application is to track people who move outside their homes within the framework of quarantine, and whether or not they are committed to quarantine procedures, and it will enable police officials to view the checkpoints from which the citizen has previously passed. This facilitates the process of tracking his movement and identifying movements that violate the requirements of the health emergency.

[5] Youm7 (2020) ‘How to use the services provided by the Egypt Health App, about Coronavirus’, 14 July, accessed 20 August 2020, https://cutt.us/uxybv.

[6] Al-Mashhad al-Araby (2020) Algeria launches a new app to face Covid-19, 31 March, accessed 20 August 2020, https://www.almashhadalaraby.com/news/172462#.

[7] Shorouk News (2020) ‘Protect, an app for following infected people in Tunisia’, 18 May, accessed 22 August 2020, https://www.shorouknews.com/news/view.aspx?cdate=18052020&id=68b2a5d9-bd6a-43b5-a6c0-9674dcf54d1e.

[8] Euronews (2020) ‘Tunisia uses robots for quarantine’ 11 April, accessed 23 August 2020, https://arabic.euronews.com/2020/04/11/police-in-tunisia-are-using-robots-to-patrol-the-streets-to-enforce-a-coronavirus-lockdown.

[9] See article 72, law no. 13-88 related to journalism and publication in Morocco.

[10] See article 1-447 Penal Code.

[11] Garside, Susanna (2020) ‘Democracy and Digital Authoritarianism: An Assessment of the EU’s External Engagement in the Promotion and Protection of Internet Freedom,’ EU Diplomacy Papers, 2020/1, pp.3-4.

[12] For more, see Naji, Mohamed (2018) ‘New Laws, The State’s stick to Control the Internet,’ Association for Freedom of Thought and Expression, 4 September, accessed 30 August 2020, https://afteegypt.org/media_freedom/2018/09/04/15714-afteegypt.html.

[13] MENA RIGHTS GROUP (2020) ‘In Covid-19, the Algerian government restricts penalties for freedom of expression and association’, 2 July, accessed 12 August 2020, https://www.menarights.org/ar/articles/fy-wst-kwfyd-19-alhkwmt-aljzayryt-tshdd-qanwn-alqwbat-ly-hsab-hryt-altbyr-wtkwyn-aljmyat.

[14] Ben Mhenni, Lina (2018) ‘While Tunisia is the first among Arab countries in terms of internet freedom, it faces another chapter of repression’, Raseef, 2 November, accessed 13 August 2020, https://cutt.us/tmUq7.

[15] Garside, S. Op Cit, p.6

[16] Anneling, Marie ‘ “The Internet is Watching You” Why and How George Orwell’s 1984 should be taught in the EFL Classroom’, Gotenburg University, Dept of Languages and Literatures/English, accessed 15 August 2020, https://gupea.ub.gu.se/bitstream/2077/33674/1/gupea_2077_33674_1.pdf.

[17] Banasiriya, Youssef (2020) ‘Arrests and social consequences, AMDH documents rights violations in the time of Corona’, accessed 1 September 2020, http://app.alyaoum24.com/1414705.html.

[18] Hussein, Mohey Eldin (2020) ‘Arab countries exploit the Corona crisis to crack down on rights,’ DW, 25 June, accessed 20 August 2020, https://cutt.us/SrrVT.

[19] (2020) Egypt arrests Sanaa Seif, sister of Alaa Abdel Fattah, DW, 24 June, accessed 29 August 2020, https://cutt.us/e2sRw.

[20] (2020) ‘After the Corona crisis report in Egypt, authorities push the Guardian correspondent to leave the country’, Arabic Post, 26 March, accessed 30 August 2020, https://cutt.us/CiUVO.

[21] (2020) ‘Despotism and the Middle East in the time of Corona’, Al-Khaleej al-Jadid, 8 April, accessed 1 September 2020, https://cutt.us/e8UwH.

[22] Zoubir, Yahia H and Anna L Jacobs (2020) ‘Will the new coronavirus change the political system in Morocco?’ Brookings, 10 May, accessed 4 September 2020, https://cutt.us/CVvRl.

[23] (2020) ‘Tunisia: blogger who shared a funny post entitled “The verse of Corona” imprisoned’, DW, 14 July, accessed 23 August 2020, https://cutt.us/7yE0a.

[24] (2020) ‘Suspended democracy in the time of coronavirus, will human rights become the victim of the pandemic?’ Al Jazeera, 30 March, accessed 20 August 2020, https://cutt.us/AJTVD.

[25] Attali, Jacques (2020) ‘History of pandemics and the changing regimes of power, what will be born next?’ translated to Arabic by Hassan Misbah, Maarif, 21 March, accessed 30 August 2020, http://maarifcenter.ma/?p=703.

[26] Zuboff, Shoshana (2019) ‘The Surveillance Threat is Not What Orwell Imagined,’ TIME, 6 June, accessed 10 September 2020, https://time.com/5602363/george-orwell-1984-anniversary-surveillance-capitalism/.

[27] Morozov, Evgeny (2020) ‘ The tech “solutions” for coronavirus take the surveillance state to the next level’, The Guardian, 15 April, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/apr/15/tech-coronavirus-surveilance-state-digital-disrupt.

[28] ‘Suspended democracy in the time of coronavirus, will human rights become the victim of the pandemic?’ Op Cit.

[29] McGee, Luke (2020) ‘Power-hungry leaders are itching to exploit the coronavirus crisis’, CNN, 1 April, accessed 12 September 2020, https://edition.cnn.com/2020/04/01/europe/coronavirus-and-the-threat-to-democracy-intl/index.html.

Read this post in: العربية